The Causality Between Orientalism and Colonialism

Introduction

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra states in his novel The First Well: “The well in life is that primordial well without which living would not have been possible. In it, experiences gather, just as water gathers to become a refuge in times of thirst. Our lives are nothing but a series of wells: at each stage we dig a new one, channeling into it the waters accumulated from the rain of the sky—that is, the burden of experiences—so that we may return to it whenever thirst overtakes us and drought strikes our land” (Jabra, 15).

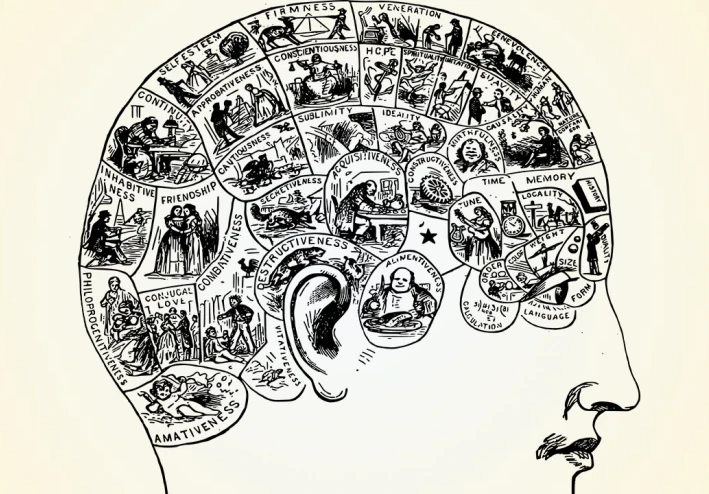

Here, the author is describing the stage of childhood, which represents the foundational phase in the formation of human character, traits, and awareness. During this stage, curiosity dominates the individual, driving an intense desire to attain the highest possible degree of knowledge through constant questioning and careful contemplation of everything that appears mysterious and open to discovery. At the same time, however, voices resonate in our minds that attempt to rebel against our very essence, persuading us that we are not truly ourselves, but rather captives of our ancestors’ history. This raises a fundamental question: is the human being a product of the self, or a product of the society that surrounds them? Does this curious child not absorb society’s ideas throughout this journey of discovery? And what, then, is the “rain of the sky” that gathers in our wells? Is it the innate rational disposition shared by all human beings, or the ancestors of humankind—their teachings, traditions, and rules?

The closest analogy to human nature is architecture: the art of planning, designing, and constructing buildings. Buildings differ in form and design according to the culture that masters this art, yet no building can acquire its essence without foundations that grant it existence. Columns are shared by all buildings, just as the human capacity for thinking and perception is shared by all people.

On The Human Nature

Although the capacity for thinking and perception is a common human faculty, individuals differ in the way they view and analyze things, incorporating them into the archive of thought. Here, a distinction must be made between thought and idea. Thought refers to the system of values, principles, and beliefs formed through experience—most of which occurs within the framework of society—and to the way a person interprets and analyzes life’s lessons. In my view, this thought and the resulting personality are shaped by two primary influences.

The first is the internal influence, saturated with curiosity. This influence is at its strongest in the first well and gradually weakens with age. It is the influence that constitutes the self. Through it, the individual gains the ability to exercise control over desires and to rely solely on reason and spirit, after nourishing them independently and without being shaped by societal teachings. For this reason, the human being may be more creative and more reconciled with the self at the beginning of life, exercising greater control over the self before undergoing formal education and before being exposed to external forces capable of exerting control, such as economics, politics, religion, and social norms.

On the other hand, from the perspective of external influences, despite the human being’s innate ability to think and perceive, it remains difficult to control the unconscious dimension of the self. This is because the unconscious does not form in a clear or comprehensible manner; rather, it crystallizes through the lessons of personal and collective experiences and through values absorbed from society in an obscure, unconscious way. Wadiʿ Saadeh states in his remarkable work Dust:

“We are not ourselves. We are history stuffed inside us. The product of the ancestors’ ideas—their teachings, rules, constraints, and prison. History is our jailer and our executioner. If this executioner celebrates, we are the puppets in his festival. If this king plays chess, we are his pawns. We are not us; we are them inhabiting us. Whoever died did not die; he lives within us, while we are dead within him. If you wish to see history, look at your face: you will see its memory and its being, and you will see your own absence. Cast it off, if you wish to be” (Saadeh, The Memory of History).

From this perspective, Wadiʿ Saadeh views us as our ancestors embodied in our own bodies. We are born under the weight of social rules established by our predecessors—alongside modern economic and political structures—and we absorb them unconsciously through daily practices, parental upbringing, and socialization. Therefore, we must reexamine ourselves and attempt to understand our unconscious in order to become capable of knowing who we truly are.

Conclusion

In conclusion, human personality cannot be formed through absolute reliance on the self alone without the contribution of society and its old and new rules, nor can it be formed solely through society without the self. The human being is a fusion of self, ancestry, and environment. Strength lies in the degree to which a person relies on the self without falling into the trap of distorted thinking shaped entirely by external influences. This strength reaches its peak during the stage of the first well and the initial formation of the self. What extinguishes the child’s curiosity to know and rely on the self is the water of society, which offers ready-made answers, laws, and beliefs on a silver platter, eliminating the need for personal reasoning and emotional engagement. Consequently, the individual drowns in the ocean of society, becoming a very small bubble within its vast waters—no longer even aspiring to become a frog that can leave this ocean whenever it wishes.